This self-replicating malware played havoc on the internet in 1988

What's the story

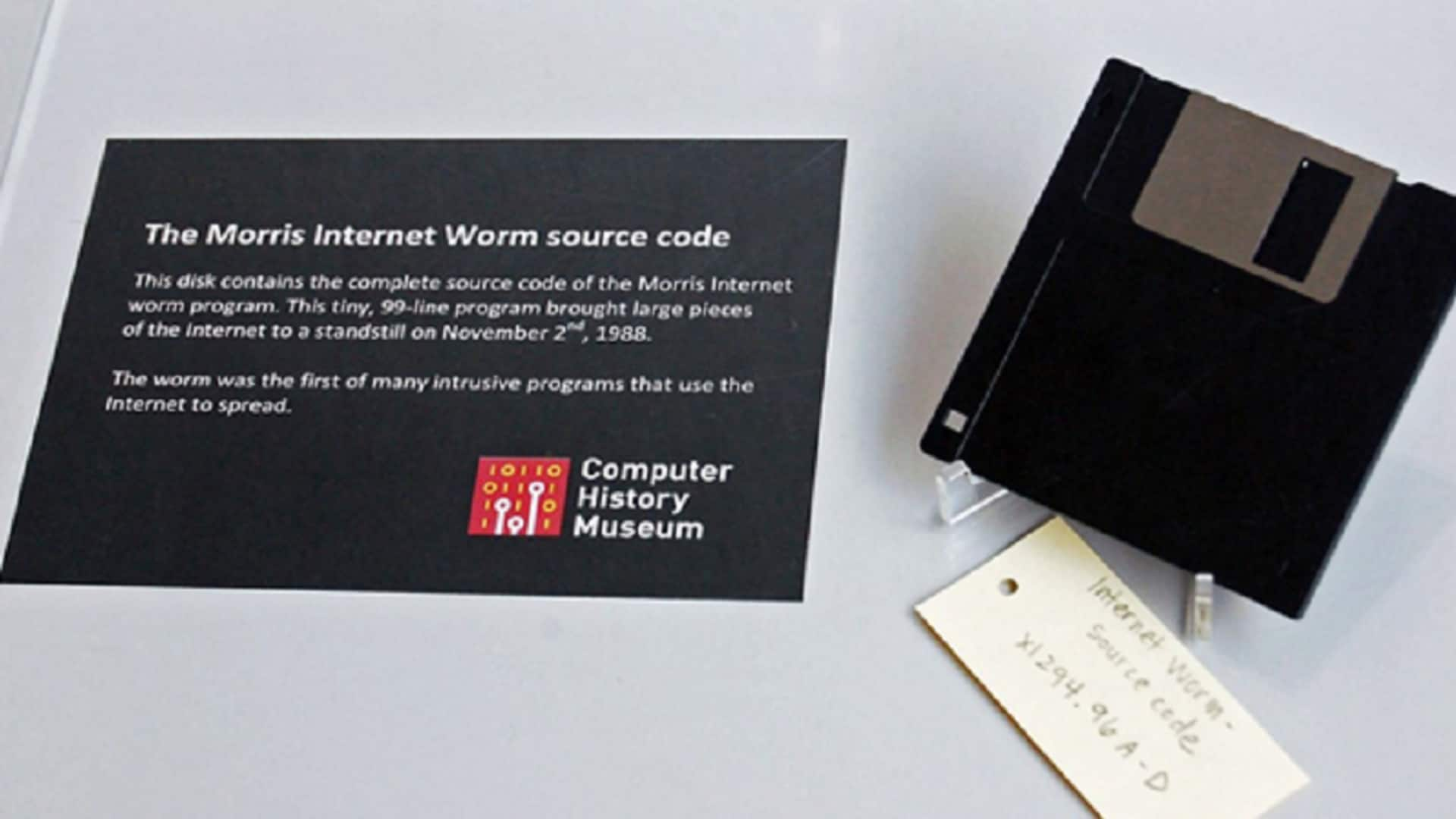

In November 1988, a new type of malware called the "Morris worm" was unleashed into the nascent internet. The brainchild of Cornell University graduate student Robert Tappan Morris, this self-replicating program quickly spread across BSD UNIX systems like VAX and Sun-3 machines. Within just one day, it had infected nearly 10% of all connected computers at the time, an estimated 6,000 out of approximately 60,000 systems.

Unintended fallout

The worm's unintended consequences

The Morris worm wasn't designed to be malicious, but it ended up causing major disruptions. It slowed down networks significantly, with many systems experiencing delays in messaging or even crashing altogether. To remove the worm quickly, some organizations had to resort to drastic measures like wiping entire systems or disconnecting networks for days. Notable victims included Berkeley, Harvard, Princeton, Stanford University, Johns Hopkins University, and NASA.

Legal repercussions

Morris was caught by the FBI

Despite his efforts to hide, Morris was eventually caught by the FBI. A friend accidentally revealed his initials, leading investigators to him. They traced the worm back to Morris's computer and confirmed he was behind it through interviews and computer file analysis. He was indicted under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act of 1986, resulting in a fine, probation, and 400 hours of community service instead of jail time.

Lasting impact

Legacy of the Morris worm

The Morris worm incident highlighted the potential dangers of self-replicating malware, paving the way for future cybersecurity measures. It also marked a significant moment in internet history as it was one of the first major cyberattacks on a global scale. Since then, computer worms have continued to evolve with technology advancements. The emergence of AI has given rise to more sophisticated threats like generative AI worms such as Morris II.