There might be a cure for deadly fungal infections

What's the story

Fungal infections, often overlooked as a major health threat, are responsible for an increasing number of hospitalizations and deaths. Beyond human health, fungi also destroy crops, lower yields, and exacerbate food insecurity. Now, researchers at the CSIR-Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology (CCMB) in Hyderabad have discovered a key insight into how fungi become pathogenic in the first place. Their research points to a potential new strategy for antifungal therapies by targeting fungal metabolism instead of just gene networks.

Shape-shifting

Shape-shifting fungi

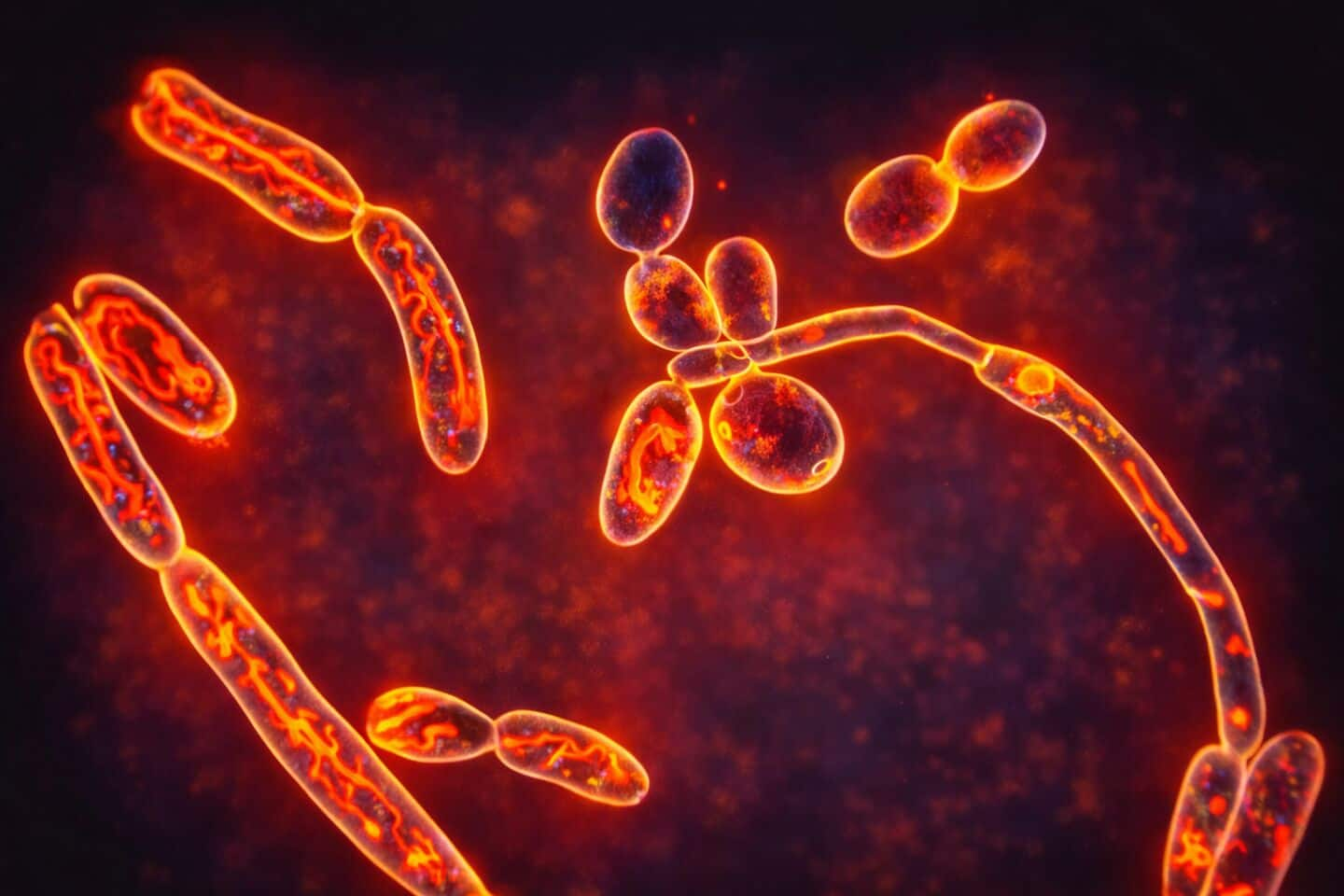

Led by scientist Sriram Varahan, the study highlights that a fungus' ability to change shapes, a major factor in its pathogenicity, is controlled not just by genetic signals but also by its metabolic processes. Fungi can exist in two main forms: a small, oval yeast form and a larger filamentous one. The yeast form travels through the host environment looking for a niche to anchor. Once it finds it, it transforms into filaments, allowing it to invade tissues aggressively.

Metabolic influence

Metabolism v/s genes

Inside the human body, fungi face nutrient deprivation, temperature changes, and competition from other microbes. These conditions generally trigger their transformation into the filamentous form, which is much harder for both immune cells and medicines to eliminate. While previous studies have focused on genes controlling these shape changes, the CCMB's research highlights metabolism as a critical driver that was previously overlooked.

Research findings

Glycolysis and invasion linked

The CCMB team discovered a direct link between glycolysis, the process of breaking down sugars, and the production of sulfur-containing amino acids required for fungal invasion. When fungi rapidly consume sugars, they produce these sulfur-based amino acids required to initiate invasive filament formation. The team found that when sugar breakdown is slowed down, the fungi remain trapped in their harmless yeast form and cannot transition into a disease-causing state.

Therapeutic implications

The 'Achilles heel'

The researchers found that when sulfur-containing amino acids were added externally, the fungi quickly regained their invasive ability. They also studied a Candida albicans strain lacking a key enzyme for sugar breakdown and found it to be "metabolically crippled." It struggled to change shape, was easily destroyed by the immune cells, and caused only mild disease in mouse models. These findings suggest that disrupting fungal metabolism could be the 'Achilles' heel' of these pathogens.