Watch: Coldest exoplanet ever discovered moves around a dead star

What's the story

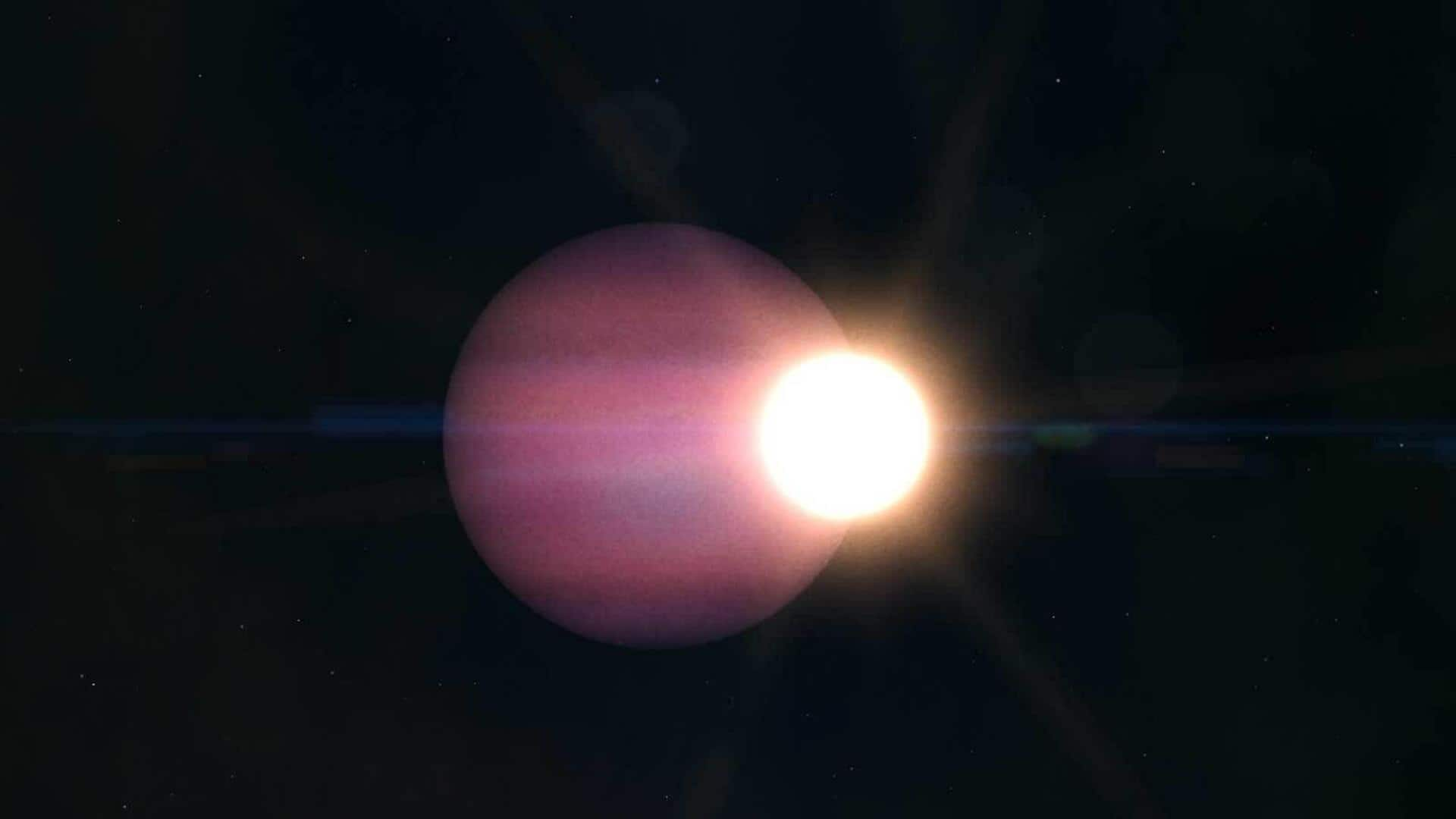

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has made a remarkable discovery, identifying the first planet known to orbit a dead star. This exoplanet, named WD 1856+534 b, is also the coldest one ever observed. The findings offer new insights into planetary evolution during the final stages of a star's life cycle. Mary Anne Limbach, an astronomer at the University of Michigan who led the new study, expressed her surprise at discovering such a cold planet.

Characteristics

WD 1856+534 b: A unique planetary discovery

WD 1856+534 b is a Jupiter-sized planet situated some 80 light-years away from Earth. It was discovered in 2020, orbiting a white dwarf every 1.4 days. At first, scientists were unsure of its classification due to limited temperature data from the Spitzer Space Telescope. However, new data from JWST provided sensitive measurements confirming it as a planet and revealing its mass and temperature.

Puzzling

Planet's survival challenges conventional theories

The fact that WD 1856+534 b survives in the "forbidden zone" of its star is especially fascinating. This area is so close to the white dwarf that any planet within should have been obliterated when the star swelled up during its red giant phase. Limbach said this finding offers strong evidence that planets can survive their star's violent death, even moving into orbits where they weren't expected to exist.

Record-breaking cold

Discovery paves way for future studies

With a temperature of -87 degree Celsius, WD 1856+534 b is the coldest planet ever directly observed. The discovery beats the previous record-holder, Epsilon Indi Ab, which has a temperature of around 2 degree Celsius. Limbach said this is a big step forward and gives an opportunity to place our solar system in a broader galactic context. Future JWST programs will look for even colder planets and their characteristics.

Future plans

Follow-up observations planned for WD 1856+534 system

Limbach and her team want to conduct a second JWST observation of the WD 1856+534 system this July. By comparing the system's position to background stars, they hope to spot any other planets that may be gravitationally bound to the star. This follow-up data will help astronomers narrow down other possible explanations of how worlds like WD 1856+534 b end up orbiting white dwarfs at such a close range.