Watch: NASA finds a possible new intermediate-mass black hole

What's the story

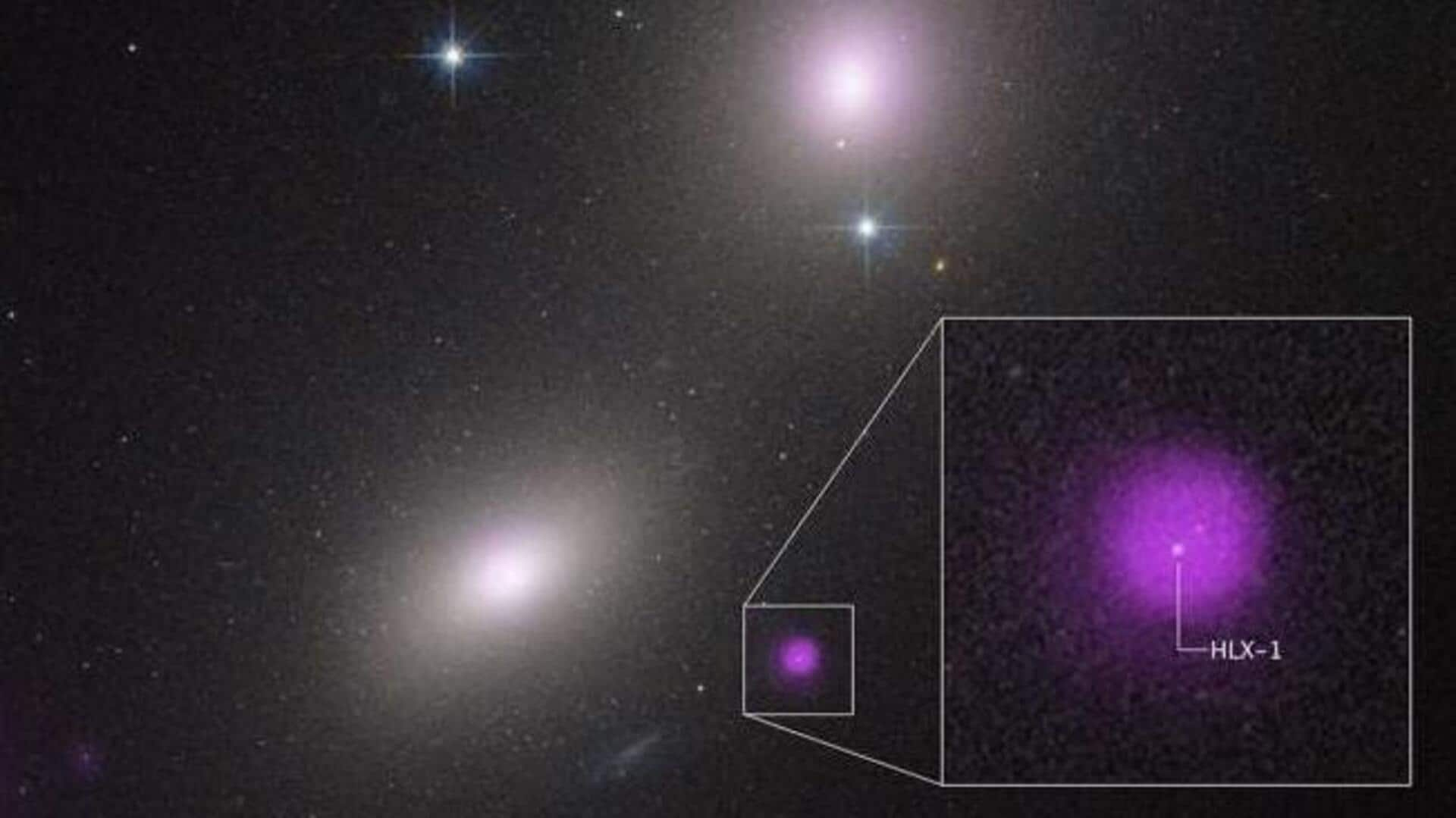

NASA's Hubble Space Telescope and Chandra X-ray Observatory have identified a potential new member of the rare intermediate-mass black hole (IMBH) class. The newly identified black hole, dubbed NGC 6099 HLX-1, is located in a compact star cluster within a massive elliptical galaxy. It was first detected as an unusual X-ray source by Chandra in 2009 and its evolution has been monitored with ESA's XMM-Newton space observatory since then.

Black hole classification

Why are IMBHs hard to find?

Intermediate-mass black holes, weighing between a few hundred and a few 100,000 times the mass of our Sun, are often invisible. This is because they don't consume as much gas and stars as their supermassive counterparts. Unlike supermassive black holes that emit powerful radiation while consuming matter, IMBHs remain hidden unless they are caught devouring a star in what astronomers call tidal disruption events.

Discovery details

Discovery of NGC 6099 HLX-1

The newly discovered potential IMBH, NGC 6099 HLX-1, is located about 40,000 light-years from the center of its host galaxy. The black hole reached peak brightness in 2012 and has been declining since then. Its X-ray emission temperature of three million degrees matches that of a tidal disruption event, further supporting its classification as an IMBH.

Feeding habits

What do the observations suggest?

Hubble observations revealed a small star cluster around the black hole, which could provide ample food due to their close proximity. The optical and X-ray observations of NGC 6099 HLX-1 do not overlap, making interpretation difficult. It could have torn apart a captured star, forming a variable plasma disk or created one that flickers as gas falls toward the black hole.

Formation theories

Why are IMBHs important?

The existence of IMBHs could provide insights into how supermassive black holes form. One theory suggests that IMBHs could be the building blocks of larger black holes, merging together as galaxies grow by consuming smaller ones. Another theory posits that gas clouds in dark-matter halos in the early universe may collapse directly into a supermassive black hole without forming stars first.

Upcoming studies

Next steps for this research

The Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile, an all-sky survey telescope from the US National Science Foundation and the Department of Energy, could spot such events in optical light hundreds of millions of light-years away. Follow-up observations with Hubble and the Webb can reveal the star cluster around the black hole. Such studies will help determine how many IMBHs exist and how often they disrupt a star.