This may be why there's no life on Mars

What's the story

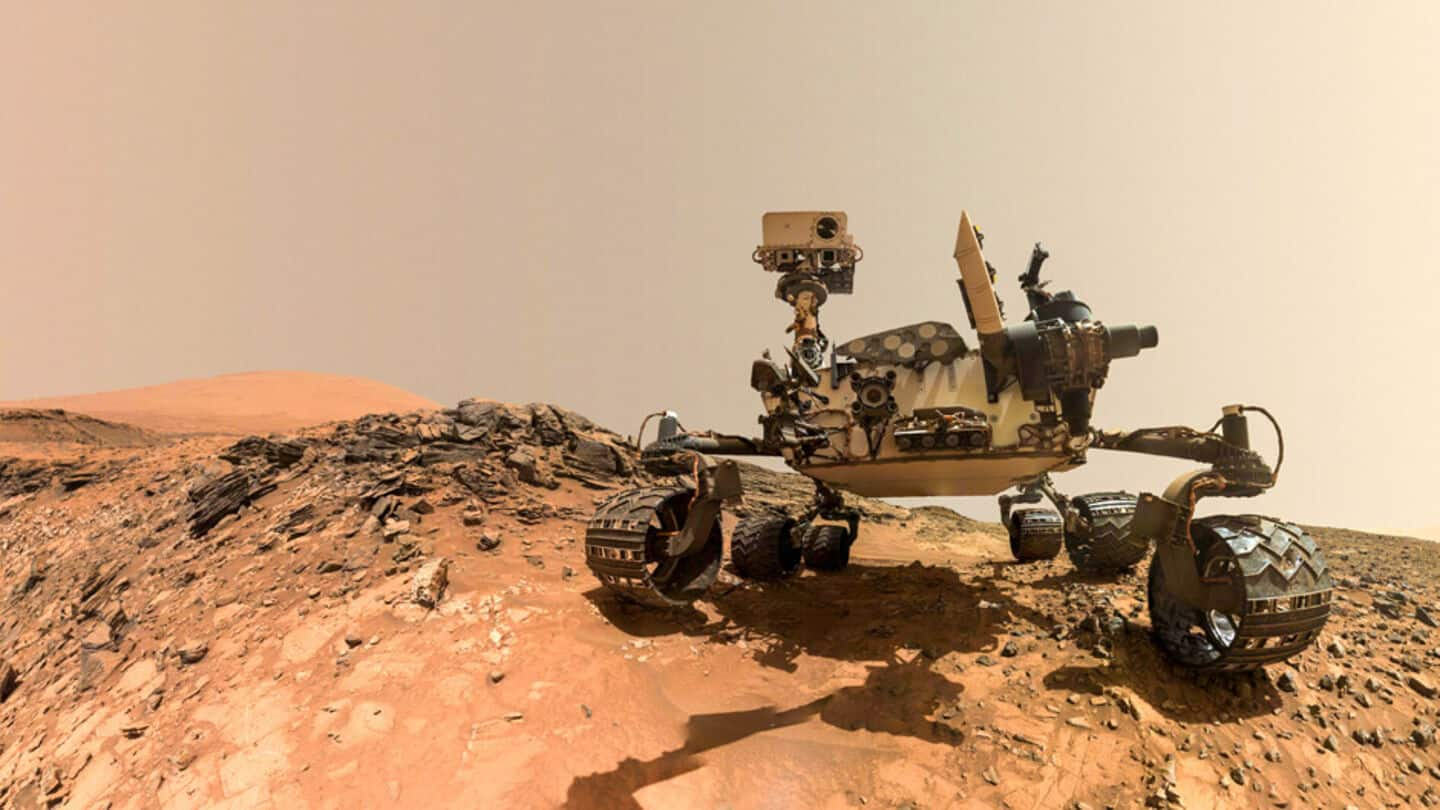

NASA's Curiosity rover has uncovered a key element in the mystery of Mars's uninhabitable nature. The research, published in the journal Nature, indicates that while rivers may have flowed intermittently on Mars, it was largely destined to be a desert planet. The study also highlights the presence of carbonate-rich rocks on the Red Planet, which could help explain its past habitability.

Geological evidence

Evidence of ancient carbonates found on Mars

The Curiosity rover discovered carbonate-rich rocks, which are minerals that can absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store it in rock. These "carbonates," similar to limestone on Earth, could change our understanding of Mars's past. Edwin Kite, a planetary scientist at the University of Chicago and a member of the Curiosity team, said these findings suggest there were "blips of habitability in some times and places" on Mars.

Climate dynamics

Differences between Earth and Mars's climate cycles

On Earth, carbon dioxide warms the planet and gets trapped in rocks like carbonates over long periods. Volcanic eruptions then release this gas back into the atmosphere, maintaining a balanced climate cycle that supports liquid water. However, Kite noted that Mars has a "feeble" rate of volcanic outgassing compared to Earth. This imbalance leaves Mars much colder and less hospitable than our home planet.

Ongoing investigations

More about the research

The modeling research suggests that the brief periods of liquid water on Mars were followed by a 100 million years of barren desert, a long time for anything to survive. However, Kite said there may still be hidden pockets of liquid water, deep underground on Mars. NASA's Perseverance rover has also found signs of carbonates at the edge of a dried-up lake, furthering our understanding of this mysterious planet's past.

Sample collection

Why return of Martian samples to Earth is necessary

Kite emphasized that the best proof of Mars's past habitability would be returning rock samples from its surface to Earth. Both the US and China are racing to do this in the next decade. These efforts could help answer one of humanity's biggest questions: how common are Earth-like planets capable of supporting life? If Mars never hosted even tiny microorganisms during its watery times, it would suggest that starting life across the universe is difficult.